Back in December, I recommended a large shipping-container company for High Yield Wealth subscribers. In less than three months, that company's shares have appreciated more than 40%.

Last month, I recommended a unique coal company that yielded 10.5%. In less than two months, that investment has returned over 11%. Due to this price appreciation, that stock's yield has fallen to 9.7%.

The shipping-container company is a safe, income-generating investment operating in a sector – global trade – that's in a long-term uptrend that should be sustained for decades to come. What's more, this company has been around for decades and has paid reliable dividends over the past 23 years.

Over the past five years, that dividend has increased at an average annual rate of 17%.

As for the coal company, its business structure – which is low-cost and high margin – makes it best in class and a reliable income producer in a sector where many companies have cut or eliminated cash distributions.

You'd think I'd be happy about these recommendations. I'm not.

To be sure, the shipping-container company is a superior company with a robust business outlook. But it's not one that should be surging ahead 40% in less than three months. I can say the same for the coal company (whose unit price is actually up 20% since late December). It may be the best coal company, but it's still a coal company for goodness sake.

Investors have been piling into stocks with renewed vigor over the past three months. The Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 were up more than 7% year-to-date before pulling back this week. Both barometers recently achieved new five-year highs.

The fact that the Dow and S&P 500 are hitting new highs isn't itself cause for concern. My issue is the high-octane rate of acceleration in the share price of many of the components of these stock-market barometers (and to be honest, many of the components in the High Yield Wealth portfolio.)

When gauging whether a market is getting overbought – and therefore riskier – I gauge a number of variables. A few center on relative valuation, and a few on sentiment.

On the sentiment side, investment bank PrinceRidge has produced an indicator I find particularly compelling. PrinceRidge aggregates four investor surveys to produce a percentage bullish composite of the market. The higher the percentage bullish trend, the lower the subsequent return on the S&P 500.

Specifically, PrinceRidge finds that the S&P 500 has averaged a 1% return over the next 26 weeks when its percentage bullish composite is above 80%. The current bullish reading is 86%.

Concurrently, many of the relative valuation metrics I follow also point to an overvalued market. The question is, why is the market becoming so overvalued, and why are so many investments shooting the moon?

To invest for income and yield is to take a marathoner's approach. Dividend or distribution increases take time, so price appreciation is usually a steady progression. Rarely will an investor find a moon shot (like Ian Wyatt’s recent trade in Netflix) in an established dividend-growth or high-yield investment. But more of these investments have produced such moon shots of late.

The Federal Reserve is the enabler, in my opinion, as well as the propellant provider.

For one, the Fed has reduced the investment choices for income investors. Bank certificates of deposit, money market funds, Treasury securities and high-grade corporate bonds barely offer a positive after-tax rate of return. This means more money has flowed into the stock market than would normally be the case.

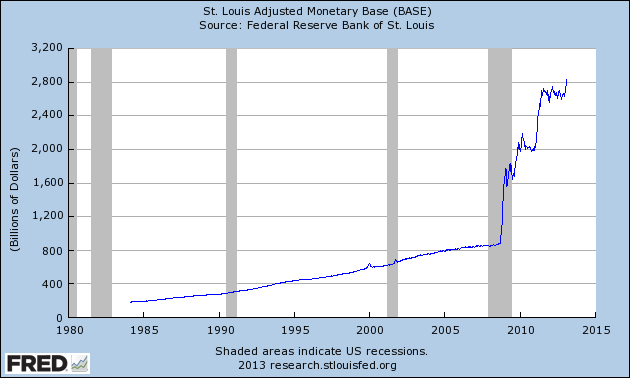

Liquidity is also playing a major role. The Fed has pumped an unprecedented amount of base money into the financial system. A large percentage of this money is held by banks at the Federal Reserve, which means it serves as a large wellspring of lending potential.

Defenders of the Fed's policies argue that the surge in base money has failed to produce a surge in loan origination – and by way of fractional reserve banking, a surge in money creation.

Actually, though, loan volumes have increased to post recession levels, and money supply continues to grow. My contention is that much of this money is finding its way into the asset market as opposed to the consumer market, which is why consumer-price inflation appears subdued.

This is important stuff for investors to understand, so I'll be exploring asset inflation, the Fed's culpability, and market risk in further detail in the March issue of High Yield Wealth.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter