Remember when the business of banking was simple?

Once upon a time, banks were places that had two primary functions: accepting deposits and making loans.

They were locally owned businesses where the teller knew your name and the president played golf at your country club. They were part of the fabric of the local community, and institutions that you could trust.

Back then, banks were invested in the financial well-being of their customers, and from that reliability came profits.

For most people, this experience is nothing more than a fleeting memory of the good old days. These days, most of us bank at one of the big banks – international financial conglomerates with far reaching activities that go well beyond taking deposits and making loans.

The big banks of Wall Street are hated because of their success. They're perceived to have taken unnecessary risks for the sake of short-term profits by expanding their businesses into credit cards, proprietary trading, hedge funds, private equity, and credit default swaps. And of course there's the most damning activity of all – issuing loans to un-creditworthy consumers in the form of subprime mortgages.

But not all U.S. banks have gotten away from the basics. There is still a small and select group of banks that keeps things simple. They are focused on the basics of banking, protecting depositors and making sensible loans to consumers and businesses.

I'm talking about regional banks. Back when I opened my first checking account at the small First National Bank & Trust Co. in southern Wisconsin, I had a personal banker. Even though my account only had a couple hundred dollars deposited, I still benefited from the personal service that made me feel as though my account mattered to the bank.

Banks like this just aren't the same as the financial conglomerates. They're independent and focused on serving their local customers.

Unlike the big Wall Street banks, regional banks continued to make money during the recession and were responsible enough not to fall victim to the lure of the subprime mortgage loan. Very few of them required a federal bailout in the form of TARP money. As a result, many regional banks are growing during a time when most big banks are still recovering from the economic downturn, and still repaying Uncle Sam.

That growth shows up in one area that holds particular appeal for investors: dividends.

Recently I recommended two regional banks that pay high-yield dividends to investors in an issue of my High Yield Wealth newsletter. One of the banks is based in Texas, the other is in Kentucky.

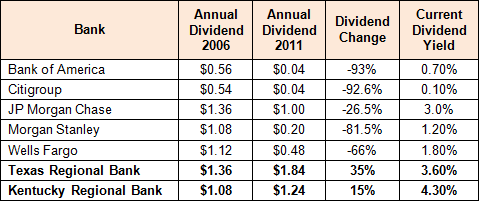

The Texas bank has grown its dividends by 13.5% a year over the last 16 years. It currently pays its shareholders $1.84 per share in annual dividends – a 3.7% dividend yield. That's up from $1.36 and a 2.36% yield five years ago.

The Kentucky bank's dividend growth is even more impressive. Its current dividend of $1.24 a share amounts to a 4.4% yield. The dividend is up 15% from $1.08 in late 2006, and the yield is nearly double the 2.53% the company paid five years ago.

Now let's compare those dividends to the big banks. Bank of America (NYSE: BAC), Citigroup (NYSE: C), JPMorgan Chase (NYSE: JPM), Morgan Stanley (NYSE: MS) and Wells Fargo (NYSE: WFC) all pay dividends that are well below the dividends of my favorite two banks.

While my favorite regional banks have been growing their dividends steadily over the last few years, big-bank dividends have been shrinking.

Added together, the average current yield among the six biggest U.S. banks – including Goldman Sachs (NYSE: GS), the one big bank whose dividends didn't drop over the last five years – is 1.37%. The average dividend yield for my two favorite regional banks is 3.95% – nearly three times the average yield of the big banks.

How were the small, hometown regional banks able to grow their dividends during a time of such turmoil for U.S. banks?

It's simple: Because they offered a safe haven where people who had fled the big banks could securely deposit their money. So many people had grown disenchanted with the big banks that they decided to take their money to smaller, more reliable regional banks that didn't require a bailout and played no role in the subprime mortgage crisis.

That's why these particular regional banks were able to improve their cash flow and increase their net worth during a time when the biggest U.S. banks were losing money.

It also helped that these outstanding regional banks were located in regions of the U.S. that have been performing better than the national average. The unemployment rate in Texas, for example, was 8.4% in October, below the national average of 9.0%. Kentucky, meanwhile, was among the top 15 states showing year-over-year employment growth in 2010, according to the Housing and Mortgage Market Review.

And the future looks bright for regional banks whereas the future success and profits of big banks may hinge on what happens in Europe. The six largest U.S. banks, including Goldman Sachs, have $50 billion in capital exposure to the massive sovereign debt racked up by Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain.

Regional banks, on the other hand, have no ties to Europe. The local banks simply don't have exposure to European sovereign debt woes – good news for income investors.

Even today, the big banks are still feeling the aftershocks of the subprime mortgage crisis. Many of them are under close watch by the federal government – something that's likely to prevent them from increasing their dividends any time soon.

Regional banks are under no such scrutiny. By sticking to the basics, regional banks churn out profits gained through customer deposits and loan payments. The result is consistent profits and little risk.

Why would you want to earn an average dividend yield of 1.37% with a bank stock that has significant exposure to the struggling global economy when you can earn three times that with a bank stock that is steadily growing its dividends and has zero global exposure?

Regional banks simply make sense. They are not too big to fail. And that's a good thing.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter