- UNG

is NOT a double inverse fund - Dancing

the contango - How

to play the trend

I’ve been teasing a full write up on why I

think the United States

Natural Gas ETF (NYSE: UNG) may have

been designed to lose money. If you’ve

had the misfortune of owning this ETF, you are keenly aware of this

tendency. In the past 9 months, the

price of natural gas climbed off the floor of $2.75 per thousand cubic feet up

to nearly $4.25 today. That’s a 55%

gain. In that same time period, UNG lost

27%.

As a reminder, UNG is NOT a double inverse ETF, but you

wouldn’t know it from looking at those results. That brings me to crux of why this ETF does not perform the way you

might expect it to, and how you can avoid making investments in similar ETFs that

are more tar-pit than gold-mine. After

all, the first rule of investing is “Don’t lose money.”

Investors typically think of ETFs as baskets

of equities, with performance naturally reflect the rise or fall of the value

of those stocks. UNG is structured a

bit differently than other ETFs available to the public. According to the United

States Natural Gas fund website:

"The

investment objective of UNG is for the changes in percentage terms of the

units’ net asset value to reflect the changes in percentage terms of the price

of natural gas delivered at the Henry Hub, Louisiana, as measured by the

changes in the price of the futures contract on natural gas traded on the New

York Mercantile Exchange that is the near month contract to expire, except when

the near month contract is within two weeks of expiration, in which case it

will be measured by the futures contract that is the next month contract to

expire, less UNG’s expenses."

Okay, that’s a mouthful.

In other words, the value of the fund is

driven by front month natural gas futures exposure. To ensure continuous

exposure, the fund’s administrators "roll" their front month futures

contracts to the next month as expiration approaches to avoid taking physical

delivery. Many ETF investors incorrectly assume that UNG attempts to track the

return of natural gas spot prices – but this couldn’t be further from the

truth.

To explain this process further, I’ve enlisted the

help of one of the best traders I know: Eric Adamowsky.

Eric explains:

”The primary

reason UNG experiences such large losses EVEN when natural gas prices rise is

the fact that the natural gas market is usually in contango. Contango is just a

fancy word that describes a situation where the future prices of natural gas

are higher than the spot prices. UNG

fund managers are forced to sell near month contracts (also known as

"rolling" contracts) for less than the cost of back month, or

second-month futures. This inevitably results in a loss of exposure to natural

gas. The UNG fund more or less pays a

"premium" to roll the contracts to the next near month to avoid

taking physical delivery. Every time they buy the next front month and

sell the current month natural gas future, they do so at a loss when prices are

in contango – which they usually are!

Contangoed

markets are generally a result of higher storage costs, as in the case of

natural gas which has extremely high storage costs. Higher future price

expectations from market participants also cause a market to become contangoed Whereas a barrel of oil can sit in a barrel

in perpetuity, if you want to store natural gas you need miles of pipeline and

humongous high-tech gas storage tanks. It

might be the most expensive commodity to store, so there are very few

circumstances when it’s not in contango.”

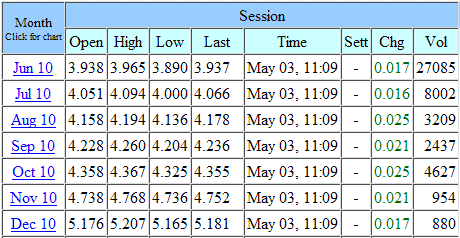

Here’s a table of contangoed nat gas prices:

Looking at this chart, you might think

“Well, I’ll buy the June future at $3.93 and sell the December contract for

$1.25 profit.”

That’s a common misconception – but what

really happens is that as you get closer to December, that contract will go

down in value. Unless there’s a huge

supply crunch or some other market disruption, your December contract will

probably come within pennies of what you paid for the June contract, as future

contract prices eventually settle to spot price levels.

Furthermore, unless you can invent a way to

store one thousand cubic feet of natural gas for free for the next 7 months, your

storage costs will gobble up any price appreciation. That’s contango: natural gas costs more in

the future, not because prices are going to necessarily go up – but because

it’s expensive to store natural gas for any period of time. The longer you hold the contract, the more

you’re paying for that storage. Natural

prices could go up, and if you own the December contract you could certainly

make some money, but prices would have to appreciate MORE than the current

contango discrepancy of $1.25.

Of course, I don’t advocate buying and

rolling natural gas futures – but that’s exactly how UNG is structured. For whatever reason, the fund is set up so

that the ONLY way it can turn a profit is if prices are not in contango, that

is, if front month prices are higher than subsequent month prices.

It can happen, and when it does, it’s called

backwardation, and it’s the result of unexpected supply and demand action in

the market for natural gas. On the inverse, if the natural gas futures are in a

state of backwardation, UNG may actually benefit from this condition. I don’t know about you, but I want to make

money from the expected, not the unexpected.

I do expect natural gas prices to rise in

the future – but UNG is not the way to take advantage of the trend. It’s counter-weighted to resist

profitability. ETFs can be a great way

to gain exposure to a variety of sectors, and not all of them are designed to

lose money, but you owe it to yourself to read and understand how they are

designed. If you don’t understand how

they’re set up for profitability, it just might be that they’re not going to be

profitable.

I’d also advise against investing in an ETF

that trades futures – unless you feel like you have a strong grasp on how they

work. Not to get into too much detail,

but every futures contract is a derivative – and some ETFs will trade options

on those contracts – which means they’re trading derivatives on

derivatives.

Why make it so complicated?

If you’re bullish on natural gas, for

instance, I recommend buying strong natural gas companies at cheap

valuations. In the Energy

World Profits portfolio, we’re currently recommending the largest

independent natural gas company in the U.S. This company has the most natural gas, with

the most active wells, and will stand to benefit immensely from any upside in

natural gas prices. If you’re interested

in finding out the name of this company, I’d like to give you a free trial

subscription to Energy World Profits. You can take me up on this offer by clicking

here now.

Good investing,

Kevin McElroy

Editor

Resource

Prospector

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter